Contiguous Storage of Grid Data for Heterogeneous Computing (Part 2)

Xiangyu Hu and Fan Gu

MeshWithGridDataPackages class

This class MeshWithGridDataPackages defines a coarse (background) mesh,

as shown from the simplified structure

template <int PKG_SIZE>

class MeshWithGridDataPackages

{

//spacing of data in data package

const Real data_spacing_;

DiscreteVariable<CellNeighborhood> cell_neighborhood_;

BKGMeshVariable<size_t> cell_package_index_;

DiscreteVariable<std::pair<size_t, int>> meta_data_cell_;

MeshVariableAssemble all_mesh_variables_;

}

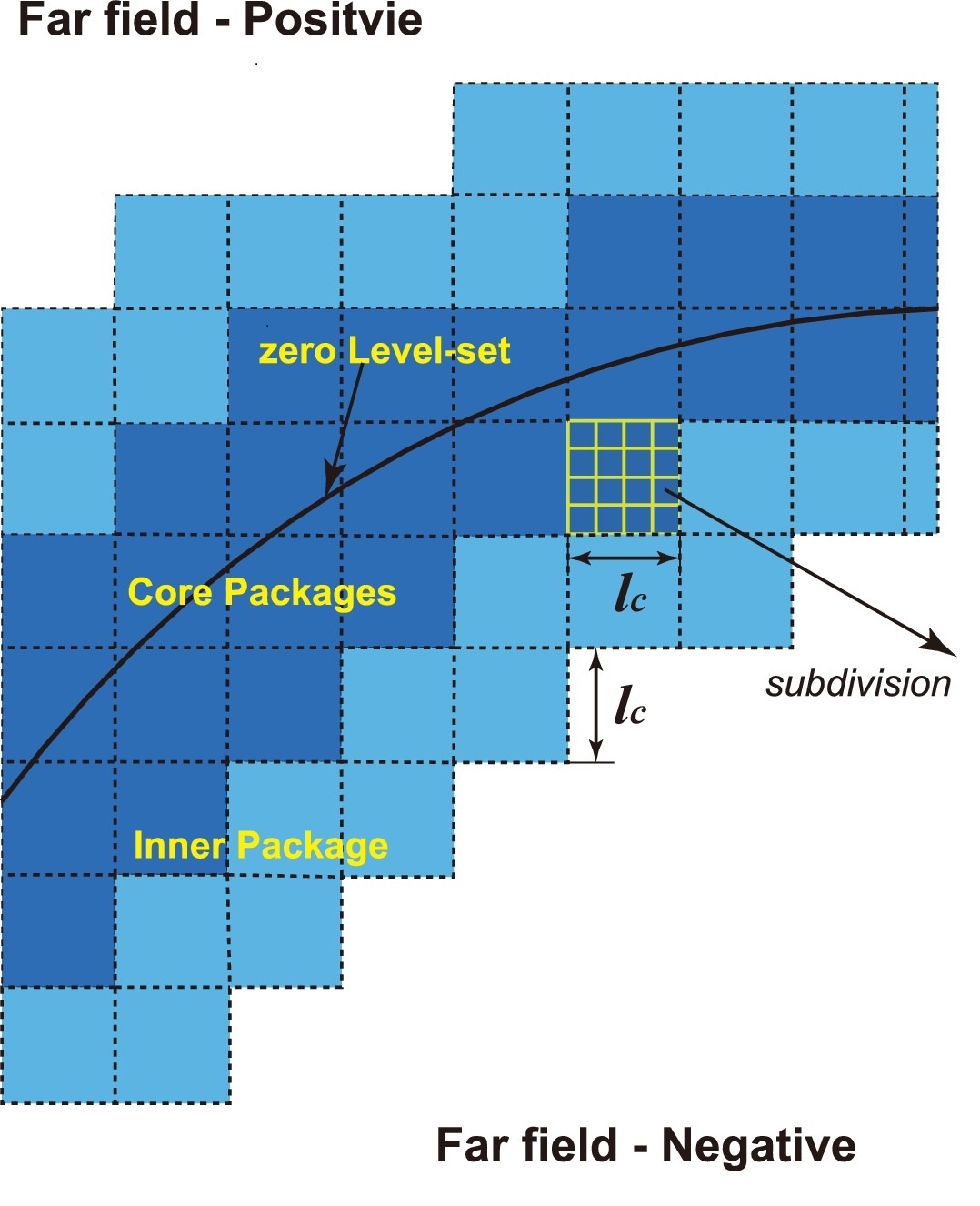

in which a portion of cells are activated (cut by the zero-level-set) and used to store refined level-set values in the form of block-data packages with a prescribed subdivision size (default by 4), as shown in Fig. 2. There are two types of data-packages: one is the core ones for describing body surface and the other inner ones used for level-set operations.

By making use of the DiscreteVariable type,

which manages 1D array of particle-wise data in SPHinXsys,

we defines three types of variables for the present method.

One is BKGMeshVariable

with the size of total number background mesh cells

for indicating the activation-status of the cells

or the index of data package if the cell is activated.

One is MeshVariable for level-set data-packages

with the size of total activated cells.

The other is MetaVariable with the same size of MeshVariable

but using simple data to define the type, cell location and topology (neighborhood)

of the data packages.

Note that, due to the coarse background mesh and the sparse activation,

the amount of memory usage for BKGMeshVariable and

MetaVariable

are negligible compared to that for MeshVariable.

With registration,

each MeshVariable is assigned with a name identifier

and inserted into the appropriate type-specific data assembly.

Retrieval operations are subsequently performed using both the variable’s type

and its assigned name.

Note that a MeshVariable must be registered prior to any usage.

A generic operation interface is provided

to enable type-agnostic operations across all registered mesh variables.

The interface currently supports two primary operations:

-

Reallocation: Upon requested, the memory for data packages is reallocated either on host or device.

-

Synchronization: Following computations on the device side, the data of mesh variables specifically registered for file output is synchronized back to the host.

Note that, these operation interface guarantees consistency across all supported data types.

Array Storage and Access

Compared to the usage of memory pool for dynamic allocation, which is fundamentally incompatible with GPU architectures, in previous SPHinXsys implementation, the present method allocates 1D array, i.e. contiguous memory for all activated data packages (actual data of all above defined variables), improving memory utilization and supporting more efficient GPU execution due to their structure-of-arrays (SoA) layout. Note that, the first two entries of the array are reserved for the two packages representing negative and positive far fields, as shown in Fig. 2, the other activated data packages is allocated after them.

Indexing

For easy direct access of the mesh variables, a indexing system is employed, comprising three types: package, cell and data indexes:

-

Package index is a unique identifier assigned to each activated cell of the mesh. It is used to index all relevant mesh variable data packages. That is, regardless of the specific data type being accessed (e.g., scalar and vector fields), the same package index will be used to retrieve data corresponding to the same activated cell.

-

Cell index is referring to the linear cell location of an activated cell of the mesh. This index plays a critical role in mapping physical space to the data packages and is essential for identifying activated cells during initialization and spatial queries.

-

Data index represents the local index of a data point within a data package, ranging from 0 to 3 by default for each dimension. It is used for accessing or modifying the mesh variable data.

These indexes work in concert to enable fast, reliable direct access to level-set data.

For example, to retrieve a data value at specific spatial location,

one would first use the cell index to locate the date package and its associated packages index.

This is then used to access data in MeshVariable,

and finally the data index identifies the specific location within the data package.

This design eliminates pointer chasing and enhances compatibility with

both CPU and GPU architectures by relying solely on array-based indexing.

Neighborhood

Level set computations, such as interpolation and stencil operations, frequently involve accessing neighboring cell data. In sparse domains, performing a full mesh lookup for neighbors at each access is inefficient. To mitigate this, the previous implementation (Yu et al. 2023) employed a larger storage matrix with a skin layer for each data package, storing explicit pointers to the data of neighboring cells in the border regions. While this approach simplified data access during computation, it imposed substantial memory overhead, especially when multiple mesh variables were involved.

The present method introduces

a more compact and scalable neighborhood storage model.

For each activated cell, a special data-package with subdivision size of 3 is

used to indicate the package indexes of the nearest neighboring packages,

enabling indirect access without storing physical addresses for each data.

When a neighboring data indicated by a shift index is required,

an access function NeighbourIndexShift, as following,

template <int PKG_SIZE>

DataPackagePair NeighbourIndexShift(

const Arrayi &shift_index, const CellNeighborhood &neighbour)

{

DataPackagePair result;

Arrayi neighbour_index = (shift_index + Arrayi::Constant(PKG_SIZE)) / PKG_SIZE;

result.first = neighbour(neighbour_index);

result.second = (shift_index + Arrayi::Constant(PKG_SIZE)) -

neighbour_index * PKG_SIZE;

return result;

}

computes the target package and data indexes based on the logical position on the mesh. This avoids storing direct memory addresses and leverages the high arithmetic throughput of modern processors.

Note that above function is only able to access the data in nearest neighbor packages. For those data beyond that, a generalized access function is designed for a two step approach by which a cell shift is determined first and then the above access function is applied to finalize the data location.

Computation Offloading

A computational operation acting on a data packages is designed as local mesh dynamics,

in respected to the corresponding term, i.e. local particle dynamics,

for the operation acting on a SPH particle.

Similarly to the usage of particle dynamics class for SPH simulation,

mesh dynamics class defines the scope of cells over

which the local dynamics should be applied.

While ALLMeshDynamics executes the computing kernel of local mesh dynamics

at each cell on the background mesh, as shown in following,

UpdateKernel *update_kernel = kernel_implementation_.getComputingKernel();

mesh_for(

ExecutionPolicy(),

MeshRange(Arrayi::Zero(), index_handler_.AllCells()),

[&](Arrayi cell_index)

{

update_kernel->update(cell_index);

});

MeshPackageDynamics does it on specific type of activated cells,

as shown in following,

UpdateKernel *update_kernel = kernel_implementation_.getComputingKernel();

int *pkg_type = dv_pkg_type_.DelegatedData(ExecutionPolicy());

package_for(

ExecutionPolicy(),

num_singular_pkgs_, sv_num_grid_pkgs_.getValue(),

[=](UnsignedInt package_index)

{

if (pkg_type[package_index] == TYPE)

update_kernel->update(package_index);

});

In this work, SYCL programming model is employed to implement execution of

computing kernels written in plain cpp style,

without the knowledge of vendor-based GPU programming models, such as CUDA or HIP.

Since SYCL functions are compatible with both host and device execution-as

long as they are defined at compile time—there

is no need for separate host and device codes of the kernel.

Provided that the data pointers are valid during execution,

the same function can be executed seamlessly on the selected SYCL device

without modification.

This design enables not only device-agnostic execution:

once the kernel function is defined and a device is selected,

it can be executed anywhere without further changes,

but also the ability of debugging and testing device codes

in a pure host-side CPU environment.

Each mesh dynamics instance contains an associated implementation object, which encapsulates the corresponding operation and is ready for dispatch to the designated execution device. Both the mesh local dynamics class and the execution policy are provided as template parameters to the mesh dynamics, enabling compile-time specialization and lazy dispatch for different operation types and target architectures.

In the next post, I will continue to give the details on the mesh local dynamics and to show how a sparse-storage multi-resolution level set field is constructed.